1.1: Intro to OS using Linux

Operating systems (OSes) are prevalent everywhere as soon as you touch anything that resembles a computer: from your smartphone, video game system interface, to the digital dashboard of your car. You, as a user, will probably never directly interact with the “bare metal”—the hardware. Even as a programmer, you’ll always have to go through the operating system and ask for permissions and so forth. In this chapter, we’ll have our first look at how this works.

The image below shows the classic picture when introducing OSes. The user never talks directly to hardware (or the OS), but always to the software.

Giving a single, clear definition of what an operating system is, is no simple job. The OS is basicaly a layer of software that is responsible for a number of things. Mainly, but certainly not exclusively, these tasks include:

- Allowing separate independent programs to use the hardware (ideally at the same time);

- Directly accessing the hardware;

- Hiding most of the complexity of the computer for the user and user-space software;

- Guaranteeing that different tasks are isolated and protected (from each other); security in general;

- …

One could say an OS is an abstraction layer that makes it easier to write software that interfaces with different types of hardware and that ensures a measure of robustness and security. By providing common services for computer programs, the OS negotiates between different layers: the hardware and the user application.

Different OSes exist for different computing platforms.

Laptops, desktops, and serversOn laptops, desktops, and servers, the most well known operating systems are used. These include: Microsoft's Windows, Linux, and MacOS. It goes without saying that there are many more operating systems for these platforms, but some/many of them are fairly unknown to the wider public. These might include: DOS, BeOS, BSD, Unix, Solaris, SunOS, ... |

Source: imimg.com |

Source: skyfilabs.com |

Embedded systemsEmbedded systems come in many flavours, colours and sizes. Typically, these devices are smaller and have fewer features than the laptops and co do. It goes without saying that the OSes that run on embedded systems are different to, or at least ported from, the other OSes. A number of OSes for embedded systems are: Android, FreeRTOS, Symbian, mbedOS, and brickOS. |

In recent years, the distinction between these types of OSes has started to fade, with systems like Android and iOS becoming more full-featured, and even low cost hardware systems like Raspberry PIs being able to run a full Linux OS.

Which operating system is the best ?

Perhaps a more interesting question:

Do you know which flavor of OS runs on:

- An Evercade system that emulates older games?

- The original Xbox and Xbox 360?

- What about the later Xbox One X/S?

- The Nokia 500 smartphone?

- Your average Virtual Private Server?

- (trick question) the Game Boy Advance?

- (trick question) An arcade system that hosts Street Fighter II?

Types of operating systems

The image above showed that the OS places itself between general software and hardware. In the most inner core of an OS resides the kernel, the heart of the OS. Depending on the type of the kernel, a typical classification of OSes can be made:

source: Wikipedia. (IPC: Inter-Process communication. VFS: Virtual Filesystem Switch)

-

A Monotlithic kernel is a kernel that runs the complete OS in kernel space. Linux is a example of an OS that uses a Monolithic kernel.

-

A Microkernel is a kernel that runs the bare minimum of an OS in kernel space. FreeRTOS is a example of an OS that uses a Microkernel.

-

A Hybrid kernel is a type of kernel that is a combination of the two types above. No surprise there, right? Windows 10 is an example of an OS that uses a Hybrid kernel

In the definition the Microkernel it states that it runs the bare minimum of software. Generally this contains the following mechanisms:

- Task management/Scheduling: the ability to run multiple programs/tasks on the same hardware at (apparently) the same time.

- Inter-Process Communication (IPC): the ability for two different programs to communicate with each other.

- Address space management: manages how the available (RAM) memory is divided between programs.

These three mechanisms form the core of an OS and will be elaborated on in the remainder of this course.

System calls

The area marked in yellow in the figure above is called the user mode. The area marked in red in the figure above is called the kernel mode or the privileged mode. A program in user mode has no direct access to the hardware or to the entire memory space: it has to go through the kernel first.

When the user, or the software on the user’s behalf, needs something from the more privileged world, the border between the user mode and kernel mode needs to be crossed. This is done using special functions that facilitate this, called System Calls. A list of all the system calls in a Linux operating system can be found here. These include methods to start a new program, send a message to a different program, read from a file, allocate memory, send a message over the network, etc.

These System Calls form the API (Application Programming Interface) between the higher-level software/applications in user mode (what you will typically write) and the lower-level features and hardware in kernel mode.

Linux

Since there are many OSes, we can of course not discuss them all. Most are however very similar in concept and in the basic systems they provide. As such, we will mainly focus on explaining these basic mechanisms in this course (see above).

Still, to be able to get some hands-on experience with these systems, we need to choose one OS: the Linux OS. We do this because it is a very advanced and stable OS that is used extensively worldwide, and because it is open source (meaning that, unlike Windows and MacOS, we can view all the code in the kernel and even change it).

The Linux kernel, available at kernel.org, almost never comes on its own but is packaged in a distribution (a.k.a. a “distro”). Such a distro is the combination of various pieces of software and the linux kernel itself. A distro can for example include a Graphical User Interface (GUI) layer, Web browsers, file management programs etc.

As such, there is a large number of Linux distributions available, which mainly differ in the additional software they provide on top of the Linux kernel (which is pretty much the same across distros). Which one to pick was (and probably is) the start of multiple programmer wars, as everyone has their own preference. Our recommendation is to take into consideration what you want to use it for. For example when using Linux on a Web server, you probably don’t need a full GUI or a Web browser, which is different from when you want to use it as your main OS on your laptop.

source: Wikimedia

If the figure above doesn’t contain a distribution to your liking you can always Do It Yourself: Linux from scratch. Happy compiling !!

One of the main aspects in which these distro’s differ is the packaging system with which it’s distributed. These packaging systems allow you to install/uninstall/… your software (a bit like the Windows Store or the mobile App Stores, but with more control over individual software libraries). The people that are making distro’s take source code from main software packets and compile them using the distro’s dependencies. This is then packaged and made available for package managers to install from. Typical examples of package mangers are:

| Name | Extension | Typical distro’s |

|---|---|---|

| dpkg | .deb | Debian and Ubuntu a.o. |

| RPM | .rpm | Red Hat, Fedora, and CentOS a.o. |

| packman | .pkg.tar.xz | Arch Linux, FeLi Linux a.o. |

If you search for Bodhi in the image above, you’ll learn that Bodhi is based on Ubuntu, which is based on Debian. Therefore APT (Advanced Package Tool) is used. This is why we used apt install SOFTWARE_NAME when setting up our Virtual Machine.

- Use apt to see a list of the installed packages in the VM

- Update the list of packages in the VM

- Install frozen-bubble in your VM and launch it with the

frozen-bubblecommand - Upgrade all packages to the most recently available version (this can take a while… Interrupting with

CTRL+C/CTRL+Zshouldn’t be dangerous, but sometimes can be!)

(tip: adding -h or –help to a Linux command typically shows you the main options. Try apt -h.)

Note that Windows nowadays also has a decent first- and third-party package manager (Chocolatey), as does MacOS (Homebrew). These systems work exactly like the above Linux package managers and can be interacted with through the command line.

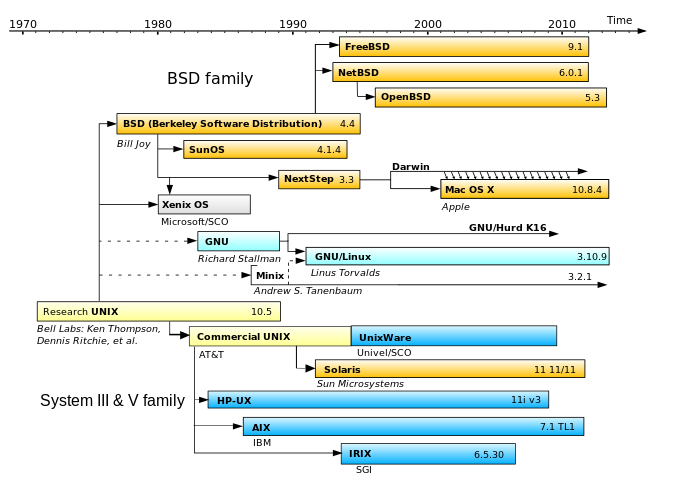

Where does Linux fit in with other UNIX-like OSes?

Good question. The huge image above merely displays different distros of the Linux OS, but Linux originated from experimental builds of the research OS called UNIX in the sixties—as does MacOS, BSD, and the like (source):

For more information on how UNIX fits within Linux and other OSes, see Awesome-UNIX.

But what about the difference between GNU/Linux and Linux?

“Linux”, as it is, is just kernel.org: the kernel on its own. A great start, but not exactly an operating system. To be a complete OS, you’ll need other applications that help managing the software on top of it. Such as a “toolchain”: compilers (GCC), makefiles, text editors (Emacs), etc—which we’ll use in chapter 2 and forward.

Modern Linux distros always come equipped with the GNU toolchain. The creator of GNU, Richard Stalman, envisioned a fully open source version of UNIX (GNU stands for “GNU’s Not UNIX!"), but by 1991, only the toolchains were done. Thanks to Linus Torvalds, the creator of the Linux kernel, finally an open source version of an OS could exist, hence GNU/Linux. The “pure” GNU kernel (GNU/Hurd on the image above) still isn’t production-ready…

Conclusion: when we talk about “Linux” as a complete OS, we actually mean GNU/Linux.

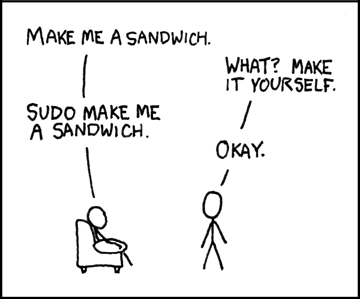

Got Root ?

Most operating systems allow for multiple users to share one system and provide ways to clearly separate those users (and what they can access) from each other. Like in most OSes, Linux also has an administrative user, or super-user: the root user, who can access -everything- on the system. This highly privileged user is typically not used when doing day-to-day work, as it can be dangerous (for example, the root user can remove all files on the hard drive with a single command).

A better way of approaching your day-to-day work on a Linux system is to use a standard user. Whenever you need a higher privilege-level, you can use sudo (Super User DO). This is a simple tool that allows a regular user to execute only certain commands as the root-user (only when needed). In your VM, your main user that you use to login with is normally also the root user, but you still need to use “sudo” to execute sensitive commands.

source: xkcd.com

Every user that has a login on a Linux system also automatically belongs to a group. Depending on the distribution, this group can have multiple names. On Bodhi for example, a new group is created for every user that bares the same name. Linux allows you to assign certain privileges and access rights to entire groups at a time, instead of only to individual users.

Find the single command that can remove all files on the hard drive online (but please don’t try it!)

Out of fuel ? Take a Shell

When a user logs in on a Linux computer, typically one of the following approaches is used:

- a login through a Graphical User Interface (GUI)

- a login through a Command Line Interface (CLI)

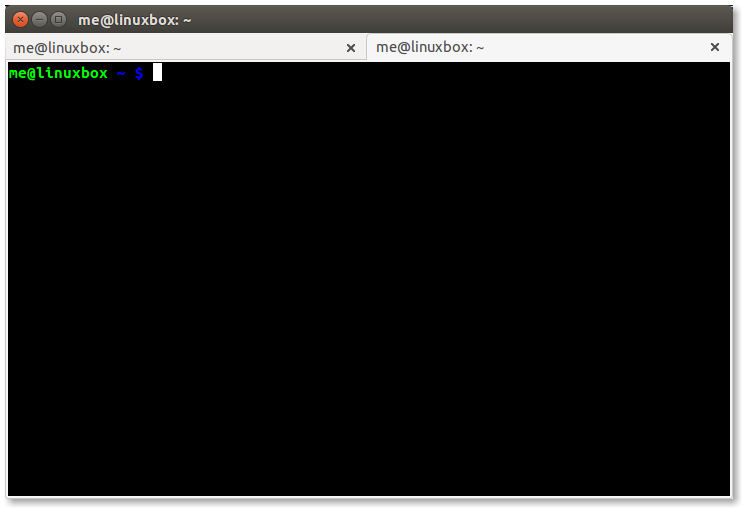

For a desktop/laptop that is running Linux, the GUI approach is typically used. An example is the Ubuntu/Bodhi Virtual Machine you use for the labs. On those systems there are terminal emulators which emulate the CLI. Many flavours of these terminals are available: gnome-terminal, xterm, konsole, …

Example of a Terminal emulator. Source: linuxcommand.org

For embedded systems or Linux running on servers, the CLI is more appropriate. Running the Graphical User Interface requires CPU time and storage. Both are scarce on an embedded system. Since everything can be done through the command line, removing the GUI is a win-win. Additionally, it is useful to learn the CLI commands even if you normally use the GUI, because they play a large part in writing automation scripts for the OS: automation scripts typically do not indicate commands like “click button at location x,y” but rather execute the necessary CLI commands directly.

No idea what terminal you’re running? No problem, echo $TERM will tell you exactly that. On my MacOS, it outputs xterm-256color (using the iTerm2 terminal).

When a CLI is used in Linux (or an emulator), a shell is started. The shell is a small program that translates commands, given by the user, and gives these translations to the OS. As with anything, there are many flavours of shells: sh, bash, ksh, fish, zsh, … Most shells provide the same basic commands, but others allow additional functionality and even full programming environments. You can write so-called “shell scripts” (typically have the file extension “.sh”), which are mostly lists of CLI commands, that are used extensively to automate operations on Linux systems.

Once the shell is running and the user asks to create new processes, all of these newly create processes will have the shell as a parent process (this will become important later on).

As a side note: Linux is not the only OS that uses a CLI. Windows for example has multiple, including the older “Command Prompt” and the more recent “Powershell”.